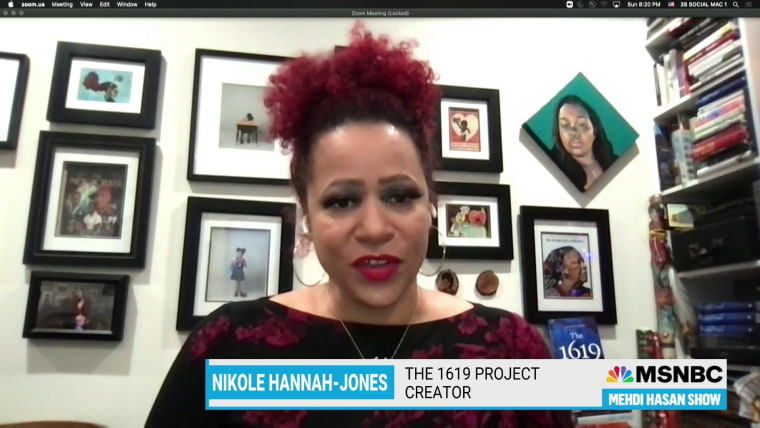

There’s a segment of America that won't deign to watch “The 1619 Project,” the six-part Hulu series that began Thursday and brings Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 2019 Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece to the screen. It’s a shame that so many Americans will refuse to watch this documentary from Hannah-Jones, a journalist with The New York Times Magazine, given the masterly curation of interviews, videos, photos and music that expands on her contention that our nation’s true founding occurred in 1619 when enslaved Africans landed in colonial America.

It is a masterly retelling of American history that, in a fair world, would be just as impactful on our image of ourselves as Americans as any documentary from Ken Burns.

“The 1619 Project” doesn’t have the gravitas of “Eyes on the Prize,” the award-winning 1987 documentary series about the civil rights movement, and it won’t grip the country the way the “Roots” miniseries did in 1977. But it is a masterly retelling of American history that, in a fair world, would be just as impactful on our image of ourselves as Americans as any documentary from Ken Burns.

But it won’t have that impact, largely because of the continuing refusal of many in white America to give up their myths of how the U.S. became the richest and most powerful country on this planet, their abject denial of African Americans’ contributions to this country and their refusal to acknowledge what Hannah-Jones and “The 1619 Project” make clear: This country owes a debt to Black people, its foundation was unpaid Black labor, and it still thrives today because of that.

The Hulu series, a faithful translation of the 2021 book “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” delves into the specifics of how slavery and Black people shaped the nation. Speaking of those Black people, Hannah-Jones says in her introduction, “It was by virtue of our bondage that we became the most American of all.”

With episode titles like “Democracy,” “Race,” “Music,” “Capitalism,” “Fear” and “Justice,” Hannah-Jones, the narrator, interviewer and guiding spirit of the documentary, starts in Jamestown, Virginia, where the story of African Americans in British North America begins. She brings us all the way to a present in which protesters are in the streets shouting, “Black Lives Matter!” The documentary is a reminder of the ongoing effects of slavery and discrimination on Black Americans, and it highlights the ways in which systems of oppression, such as housing discrimination and mass incarceration, continue to affect Black communities today.

That having been said, if you have a passing knowledge of African American history, have read the previous iterations of “The 1619 Project” or have just been paying attention to the news in the U.S. over the last decade, you aren’t going to learn much that’s new.

Hannah-Jones does tell an intensely personal story about her life as a Black woman raised in the U.S. with a white mother and a Black father.

Hannah-Jones does, however, tell an intensely personal story about her family and about her life as a Black woman raised in the U.S. with a white mother and a Black father. She describes how racism, sexism and classism affected their lives: not just in her father’s birthplace in Mississippi, but also in Iowa, where she grew up. Although the insertion of her own stories into this reframing of American history can seem jarring at times, it does help ground those larger stories and serves as a fitting rebuttal to the criticism that she’s needlessly describing historical events that happened years ago to unnamed people and that those events have had no impact on people today.

Since the release of the New York Times Magazine piece in 2019, critics have attacked the project and Hannah-Jones herself, accusing her of inaccurately reframing American history to improperly put the Black experience squarely in the middle. Several states have gone as far as to ban schools from using any iteration of “The 1619 Project” or similar items in the classrooms, hoping to shield from their students’ eyes an accurate depiction of American history in favor of the historical myths that have long been promoted. But those critics have refused to acknowledge that the history they defend was written by white people and that it purposely downplayed the role of slavery and Black Americans in the country.

In this documentary project, we see the people behind the stories. We hear their voices. That should make a major difference in how this work is accepted. It should help make real for those who have doubted it the inaccuracy of the white-male-centered framing of U.S. history.

Critics have attacked Hannah-Jones in part by pointing out that she’s not a historian and by questioning her expertise, but except when she’s talking about her own family history, she doesn’t present herself as the expert on the issues being discussed. She’s clear about what she is: a journalist. In almost every scene she’s in, she has her trusty notebook and her list of questions, and she does what every good journalist does: She finds the experts, allows them to explain the facts and then weaves their information into a coherent narrative arc that leaves the viewer with a clearer understanding of the subject.

To repeat, the sad thing about this masterly work is that the people who need to see it won’t watch it, just as they refused to read it when it was first printed. But “The 1619 Project” is well-told, and it can help those who approach it openly and honestly better understand how this country came to be and how the way it all started is still a factor in the way we are today.