I started executive coaching Milwaukee-based marketing executive Andrea Woda and her team in 2019. She was hoping I could work with her two male colleagues whom she faulted for poor communication and a reactive culture. What I uncovered in coaching with Woda was a classic case of it’s a “them-not-me” problem.

Woda was perceived as low drama, she flew under the radar and didn’t recognize how she created issues at work. While the team struggled with communication, they were close and related like family. Woda had a strong work ethic and prided herself on her loyalty, integrity, and consistency, but there were other dynamics at play.

To uncover the underlying dysfunction that affected their productivity, I had each team member take a DISC behavioral assessment. It’s a psychological tool used to measure how the brain absorbs information and creates the behaviors that define your personality type (strengths, weaknesses, stressors, conflict management style).

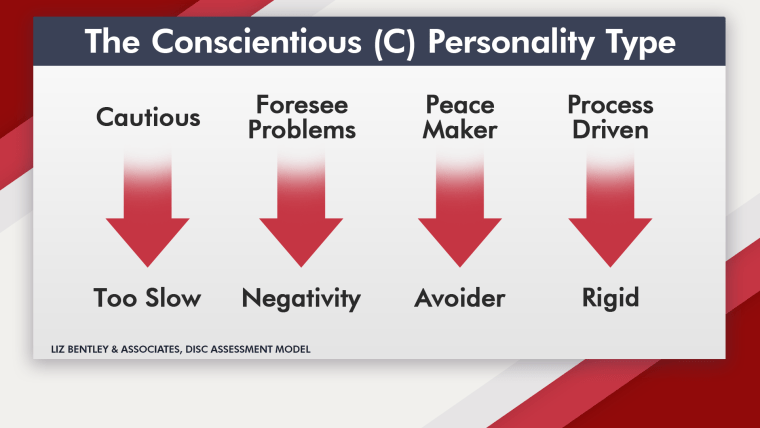

Woda’s assessment identified her in the Conscientious (C) personality type. On good days she is analytical, process-driven, accurate and detail oriented. She thinks before speaking and she is tactful.

On bad days, she is too cautious, slow or can’t get started. She can be inflexible, miss the big picture and turn passive aggressive when uncomfortable. While Andrea prided herself in picking and choosing her battles carefully, I found she was not picking the important ones. Too often she would remain quiet when she should have been speaking up. Unknowingly, her passive personality style was contributing to why the team was stuck.

The imprinting years

In my work, it is critical to understand my client’s imprinting years – the first 10 years of life. These formative years create the blueprint of our character, dictate our mindset and set behaviors, both good and bad.

Woda grew up in a small Wisconsin town of only 2,000 people. She was the oldest of three children – the only girl – with two rambunctious brothers. Her father went to work every day, her mother was a homemaker. She had a simple and pleasurable childhood, succeeding in school without taking much risk or being pushed out of her comfort zone. Woda described her younger self this way: responsible, easy and smart. For her, the status quo seemed good enough.

When strengths go south: Quiet quitting

With her background in mind, I used a coaching model I call “Strengths going south.” We all have strengths that sometimes manifest as weaknesses. For example, our ability to be direct can turn hurtful, our optimism can be unrealistic, and our desire for peace-making can bury the truth. Woda’s thoroughness was making her too slow; her ability to fault find was making her too critical; her non-confrontational nature was making her passive aggressive; and her process-driven approach was making her inflexible to change.

Her two male partners were Dominant (D) personality types. They liked to steer the conversations, make the decisions, and jump quickly into action. Peter, the team leader, also had great vision and a lot of ideas, but the team was disorganized and couldn’t execute on out-of-the-box solutions.

Woda adopted a negative mindset loop of seeing fault more than opportunity. And like most “C” personality styles, she liked to be right. This made her overly critical, focusing on what was wrong with everyone and every idea.

Essentially, she was quiet quitting – giving up in her mind and not really showing up all in. She didn’t take ownership of the outcome of her work or initiate change within the team. Instead, she kept her thoughts to herself and become more passive aggressive.

That led to inertia, withholding information that subtly sabotaged projects and people, avoiding urgency and instead, gossiping to others about team problems.

Mindset shift: Owning struggles, escaping perfection

Woda admitted the difficulty in hearing where she was failing and needed improvement. She, like all of my clients, had to put her ego aside to see how see how her weaknesses were sabotaging herself and others.

We began to shift her mindset and behavior one area at a time, starting with her non-committal language. She would say “sure” a lot instead of “yes” or “no.” Her project was to delete the passive “sure” from her vocabulary and either go all in with a “yes” to a commitment or disagree with a “no” say why. The exercise forced her to push back, own responsibilities, engage all in and get out of victimhood.

Next, we tackled the perfectionism trap. For the “C” personality type, this looks like needing all the information in order to start a project; needing more time to think through every conceivable option and downplaying the urgency of timeliness.

She couldn’t see the big picture or negative impact of her slow speed. Letting go of perfection allowed her to get started and adjust along the way. As a result, she became more collaborative, took on more risks and asked for input at the beginning of the project. Engaging others made her more open minded and less controlling.

Stepping out of her comfort zone

Woda’s childhood identity prevented her from challenging the status quo. Through coaching, a big “aha” moment was recognizing how the different personality styles approach language, problem solving, and idea generation.

Woda’s “C” style is to think carefully before speaking, her teammates “D” Style was to think out loud by talking out their thinking. This realization reduced her frustration in conversations and she was able to embrace it as brainstorming.

She began to prioritize deadlines and saw that work was being accomplished and successful even if it wasn’t perfect.

Stepping into her power

Woda’s childhood descriptors of being easy, responsible, and smart kept her from developing her full potential. This compromised her leadership. She let the men dominate overtly and got her power covertly, through passive aggressiveness.

Through coaching, she shifted the meaning of those three adjectives. Her ability to be “easy” was no longer about acquiescing but being open-minded to different perspectives and getting started without a full plan.

Her being “responsible” was not about just doing what she was told but owning the outcome and result of her projects, holding others accountable and addressing conflict directly.

Lastly, her ability to be “smart” was no longer valued in perfection but in her ability to see people differently, problem solve more holistically and move faster.

Woda realized that owning her struggles gave her the ability to hurdle them and grow her confidence. Confidence, in turn, gave her the power to see that her excuses were just that – excuses – which made it was easier to let them go and embrace a healthy habit cycle.

As she puts it, “I now know my value more than ever before.”