Through public health advancements and education, such as nutrition, cleaner air and water, immunization, prevention of chronic diseases, and improved maternal and child health, we have added an extra 30 years to our lifespans.

That’s 30 years longer than we lived 100 years ago, creating a whole new stage of life. But we are woefully unprepared to take advantage of these three bonus decades. While we have mastered the art of extending our chronological years, our society – our culture, infrastructure, workforce and economy – is ill-equipped to support the healthspan of our new lifespan.

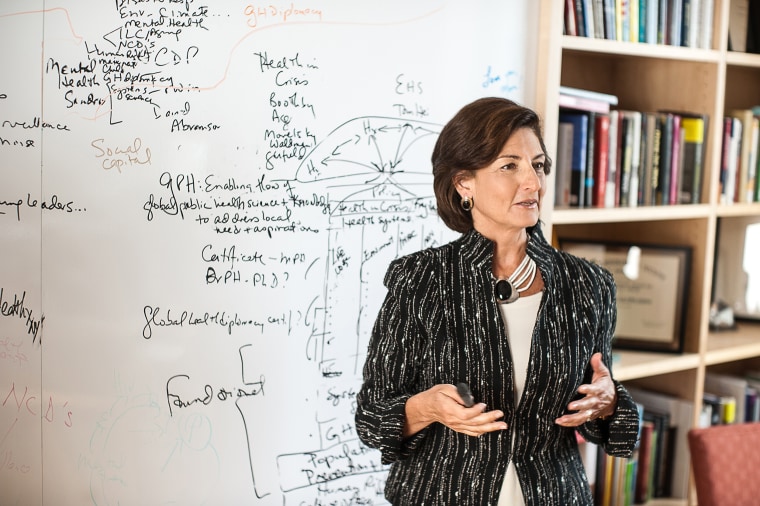

In the Columbia University class “(Y)our Longer Life,” that I co-teach with Dr. Dana Palmer, we examine the meaning and opportunities of aging and the attendant expectations, myths, fears and realities.

We explore the physical, cognitive and psychological aspects of aging, from the attributes and challenges of aging, to the keys of aging successfully.

Our students – graduate, undergraduate and adult auditors – are challenged to find ways to maximize their own lives and identify ways society must catch up with the science.

The U.S. National Academy of Medicine’s Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity offers recommendations to help aging societies thrive. But there are things we can do as individuals to take charge of our own aging to help make our longer lives happy and productive.

Many factors impact the quality of our longevity. Genetics play a role and we’ve heard about the benefits of a good diet and regular exercise. But recent research shows us that there are other factors we continue to learn more about.

For example, Dr. Dan Belsky, a guest lecturer in our course, has conducted research that shows that childhood stress and trauma can hasten biological aging. Other research has found that later-in-life education, volunteering and staying physically active can all help prevent cognitive decline.

A throughline of the course is a set of “prescriptions” students create for every future decade of their lives, the consideration of the fact that it’s never too late or too early to fashion your own “health future.” That can look like volunteering or starting to exercise in your 60s, returning to the classroom at 52, quitting smoking at 40, learning to drive at 35 or starting an investment plan at 22.

One of the most popular assignments in the class is, ironically, studying obituaries – stories of lives well-lived. While at first blush it may sound a bit morbid, students find inspiration for their own lives studying the accomplishments of people in their later years. Oddly, when looked at with clear eyes, these obits are life-affirming, reflecting our potential at any age.

Consider writing a “prescription” for your own life, or even your own obituary to help identify your goals. Although our goals can evolve as we change, the sooner we can pinpoint them, the better shot we have to achieve them.

As our lifespans have changed, so have our lifestyles. At one time people worked for the same company throughout their careers, whereas today the typical millennial will have four to five careers and perhaps up to 15 jobs. The road to our goals is very different than it was 30 years ago, but the rewards of achieving them remain joyous and fulfilling.

As you prepare your “prescriptions,” consider that our lives are generally divided into three parts:

- Childhood education

- Adulthood working

- Aging retirement

To get started, below are examples of prescriptions written by my colleagues and students:

Prescription for Your 20s:

Become financially literate and begin a savings plan for retirement, save for a home, and begin to pay down student debt. Most students today will be in debt and unable to own the type of home their parents did. And most have not begun to save for retirement, which will be more acutely needed due to longer lifespans.

Prescription for Your 30s:

Evaluate your career path. Take stock of your personal goals, including relationships. Dissatisfied with your career? It might be a good time to change. Do you have intergenerational relationships with older people? Consider the experience and wisdom that older people bring to the table – not their vulnerabilities.

Prescription for Your 40s:

Is it time for a sabbatical? A return to school for another degree to enhance your career? Is it time to spend more time with your aging parents? Typically, the 40s are a demanding time of career and family. Taking a well-deserved break can help with a different perspective and re-evaluate priorities.

Prescription for Your 50s and 60s:

Don’t retire. Think about a new type of engagement you might have. A new, more flexible job? Volunteering?

Go back to school. Is education wasted on the young? Learning something new can help prevent cognitive decline, build community and offer new job possibilities.

Find community. Loneliness can be as deadly as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Join a book club, start playing pickleball or find a new hobby where you are around people and engaged in a common purpose.

As we age it is important not to allow myths and fear to limit us, particularly for women who are subjected to double standards around beauty and youth. Challenge those stereotypes. Talk about them. Push back. Older people don’t have to be alone; commit to staying socially and cognitively engaged.

Our society must do a better job of valuing the contributions of older people. In our class, we work to debunk the negative stereotypes associated with age. Students think about the language often used to describe older people: sick, lonely, sad, weak.

Through our empathy-raising exercises, such as writing their “prescriptions,” by the end of the semester they are replaced with words like these: knowledgeable, experienced, wise, generous and powerful.

Not a bad goal for all of us.